The Right to Read Female Writers | Leopoldo Brizuela

“Reading women was a way of transforming our Homeric burdens of pain, hatred and violence into a new, and alternative, productive force” says the author of “Inglaterra. una fábula y de Una misma noche.”

Ever since I first started writing and, especially since I began to publish and to speak publicly about my readings, friends, colleagues, journalists and critics have all asked me the same question: “Why do you read so many female authors?” This was a question that always bothered me enough to answer it, vaguely, with evasive answers. As if speaking the truth – a truth which I myself was barely conscious of, by having never discussed it – could expose me to the worst kind of danger.

I used to babble: “Well, I didn’t mention that many.’ And it was true; this reproach would happen at the second or third citation of a female author, but that was already more than the person in question knew, or seemed cautious about knowing. At times, I would pretend to take up the gauntlet, in a challenge I knew I would end up abandoning: “If I had mentioned only male authors, would you have made a note of it?” Obviously they wouldn´t have. Neither would this speaker have accused female authors who only cite male writers of ignorance, nor the female critics or professors who only include the works of male writers in their syllabuses, anthologies and essays.

But I wouldn’t respond, and the other person, spurred on, as if they had unearthed some ruse or conspiracy, would conclude: “I ask you simply because it’s strange.” In short, they were the self-proclaimed representative or arbitrator of normality, and everything seemed to return to the subject of ‘her’. This had reminded me, and it was their victory, of the law that governs all of us, men and women: only he who conceals his true nature survives.

Two ways

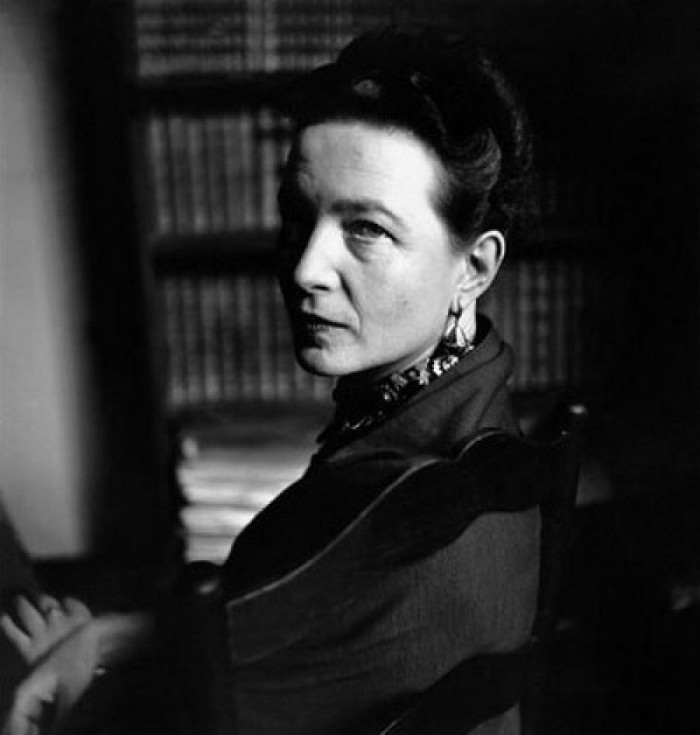

First exception. Perhaps I haven’t dared, until now, to answer this question clearly, due to lacking any guidance beyond the books of these same female writers. Because to formulate in theoretic terms what the apathy that the protagonists in Jean Rhys’ works, or the radiance of Doris Lessing’s heroines, had taught me, or to demonstrate why Simone de Beauvoir or Adrienne Rich’s reflections on “The Second Sex” could also be applied to my own experience, was a task that went beyond my capabilities. Nowadays, however, we take into account various theories on the construction of masculinity; and these might help me explain how violence and terror, running dormant beneath the same repeated scenario, put down roots in infancy.

Specialists say that in societies like ours, he who distances himself from his mother “becomes a man”; the man is thrown from the house, to school or the street, to take up another, far more important, kind of training than the kind which any schools foster: masculinity, a social position that is a currency in itself and which will enable him to occupy, for the rest of his life, spaces of power within the patriarchy. As Ariel Sanchez explains in “Marcar la Cancha¨ this training is carried out in two ways. On the one hand, the man seeks out a group of men through which he might be able to acquire and build up strength, recognised by his ability to exercise violence over the rest. Through basic means of competition, and the amount of force that enables this, hierarchies within the group are established. It is the loyalty to this group, and to its hierarchies, that can be understood as a true condition of existence.

On the other hand, the construction of masculinity relies on finding someone to designate or label as a ‘poof’ (maricón.) Through means of permanent harassment, the man will hope to show his rejection of anything ‘feminine’, thereby definitively estranging himself from his mother. As anyone my age will remember, for children of the 1960´s the nickname “maricón” didn’t need to have any particular connection to homosexuality – the mere idea of ‘sexuality’ was alien to our world then -but instead it was tied to some characteristic in their personality that other men would identify as feminine. These were surprisingly varied characteristics – it could be anything from having a way of moving or speaking, to a physical trait, or more specifically, as my older friends tell me now, a fondness for reading -but it all seemed to be linked to a lack of physical force or a dissidence regarding the use of force.

And yet the immorality in harassing the ‘maricón’ lies in the fact that, as it is all too easy to exercise violence over the weak – so much more so when it is the group itself that has hampered the development of his strength – what the attacker demonstrates here is more the infinite, deep-rooted vileness of a particular social framework than his own masculinity. And so, in the search for some impossible demonstration of masculinity, violence is perpetrated on a daily and incessant basis against the designated ‘maricón’, or ‘poof’, causing trauma in its victims throughout life. Our society seems finally to be opening its eyes to this, but it is a trauma which, throughout history, had almost no other release than through literature.

Life and literature.

Second exception. Perhaps the question -“why do you read so many women?”- would have bothered me less if I had begun to do so out of some kind of political strategy or careful consideration. No. We began reading female writers ‘spontaneously’, let’s say, like a hunted animal that suddenly discovered the only place in the world that reminded it of its first lair; but it was there where we found, almost by surprise, permission to be something that was always forbidden for us, and the weapons to achieve this.

To the horror of those who maintain that the only important thing is text, we are never just searching for books: we would search for authors about whose experience, beyond the enigma of their works, we might venture our own guesses. And how could a woman’s name on a book cover not be of interest to us when it offered proof that, in societies even more oppressive than our own, the writer had done something that nobody else had ever expected of her? How, when, at a time when her own contemporaries failed to understand her, she had paid a high price for speaking out to her “future sibling”— namely, us, today? If a film propelled us to feel sympathy for Anne Frank and her tragic death, something that would forever captivate us in her diary entries was her decision to sustain, in the face of suffocating constraints in her political and familiar confinement, the desire to talk to herself, and in doing so, to become a writer. If a song composed by two men told us of Alfonsina Storni’s suicide, the cover of the first book that we asked them to buy for us compelled us to read each of her poems as another creation, undesired by men and saved by her absolute vigilance.

Of course, beyond that same question -“but why do you read so many women”- we could interpret the subtext: “they aren’t that good.” But we have already seen how literature written by women has always possessed values that few men could appreciate; namely, a flair for invention and the use of tools that represented, discreetly, feelings of discomfort and rebellion. In producing this unique experience that we call “art”, they not only provide us with aesthetic enjoyment, but also stir in us a profound transformation in the way we perceive reality. So, although few men might grasp this, one particular phrase of Carson McCullers’ (almost the first in her initial novel) – ” In the town there were two mutes and they were always together” –could generate an aesthetic experience infinitely richer than all of Ernest Hemingway’s tales, with their displays of macho firing off between soldiers, gangsters, hunters and bullfighters.

And if, as Giles Deleuze says, writing literature is the invention of a foreign language within language, and if the task of women has been to subvert masculine convention through poetry, who better to demonstrate this than Sara Gallardo with her Matacoan Eisejuaz; this innocent or mad character that is her alter ego, this obsolete creation, capable of suggesting- in a new language- everything which Argentine culture had not yet managed to define.

A secret force

I think I have already begun to respond to the question. Reading women was a way of transforming our “Homeric burdens of pain, hatred and violence” into a new, and alternative, constructive force. And perhaps the moment has come to describe this, so as not to overvalue it or expose myself to a greater danger. For the time being, what is it really about? In principle, I think that every person who has been labeled a ‘poof’, or ’fag’, or ‘maricón’ and has survived infancy, manages to distance themselves and understand not only why these violent acts are directed at them, but also the fears and weaknesses that, secretly, torment their attackers.

In this sense, from very early on, I have seen my fellow writers as the children that they were, devoted in the exhausting task of demonstrating their power, and exercising it in those same two ways. Look at them in any literature conference; how they camouflage themselves, how they compete, how they try to seduce. They overplay their masculinity, perhaps because, let’s face it, poetry isn’t the skill that a military officer wanted for his firstborn son. Listen to the way they speak! Perhaps it would be excessive to ask them to have a conversation with one another… Influenced and wired by the world of football, their chief concern is joining a team under the wings of a ‘technical director’ who can tell them what, and how, to write in such a way that each word might offer proof of their manliness. And they speak of the “literary field” in the same way one would of a pitch where a tournament has come to be played; of winning prizes like ‘passing a ball’, ‘scoring’ books in an important publishing firm, or an article in mainstream media, in the same way we’d refer to goals. And of course, every now and again, they cite female writers (why not?); but the ones named are always women who, happy to remain enslaved in the role culturally assigned to them, serve to exemplify old, tired categories, women who cheer them on like the most sophisticated cheerleaders in history.

Secondly, guided by these ‘technical directors,’ who are always expert in the art of shaming, these men do their best at pointing out ‘literature’s maricónes’ – those who shouldn’t exist – and queer literature, which shouldn’t be written. Nowadays, just as before, “queer” or “maricón” doesn’t necessarily have to correspond with the sexual choice of a writer, but with stereotypes of femininity. These characteristics are overwhelmingly varied – they belong to such vast and distant cultural camps that, by rejecting them, the majority of men are marked by their shocking ignorance. But returning to our theme: the men poke fun at, for example, admiration that ‘maricónes’ or ‘queers’ have for female writers, as if it was nothing more than a variation on the criminal love they have for their own mother. They don’t see that, as Wayne Koesterbaum notes, what the ‘queer’ celebrates in ‘divas’ is an excess in voice, comparable only, in its magnitude, to their own impossibility for speech, and the lost tradition that this diva’s voice returns, with a raging and surprising vitality. These guys laugh at ‘queers’ for the frankness with which they wish to express their feelings, mechanically identifying these as something ‘kitsch’, which queer culture celebrates so much. Their affliction is repression (a similar working to shame, but something which goes beyond this, because it is the self inflicted punishment for their ‘feminine’ side); these men block out their own inability to deal with their feelings, and their laughter is the little they can do with this desperation. But they are desperate – it’s obvious – and they have ‘naturalised’ their ignorance to the point that it feels like a trait with its own identity. For every unknown thing they encounter, they fail to spot its potential to enrich their own lives, instead viewing it as a threat of their own undoing. Proof, then, that we still have to exercise caution, because there is nothing more violent than a ‘denier’ who is trapped.

A necessity and a right.

Why, then, do we read the works of women? Because it is a necessity, perhaps our deepest necessity and where there is a need, there is a right. It is the right of an entire tradition that has survived. A right that strengthens and is liberated when we read, and when we respond to reading with our own works. For, however much that we might try to convince ourselves that everything is different now, as if the utopia of old feminism was the only thing we were in search of, this change only affects our social customs, at surface level. It doesn’t penetrate beyond this, or reach us at the deepest level —our minds.

How in a world in which, nowadays, nothing stands in the way of free sexual intercourse between two consenting adults, can we explain that men continue to flourish, in secret, not just as dealers but also clients of sexual exploitation? No less enigmatic is the remaining question of why, when although many of the great books throughout literature have been written by women, and although women might be in the majority in the fields of printing, publishing, literary workshops etc, is the presence of a woman in literature still considered an anomaly?

What to do about these men’s blindness? There are those who think that change is impossible, or only possible in the case of the most remote genetic mutation, and that our task is to fight. Yet how we do so remains fairly inconceivable and, in any case, the lack of fundamental equality between us still assures us of immediate defeat. Others maintain that the way forward is through persuading, forgetting that persuasion, as Hannah Arendt notes, is only possible between two human beings of equal footing, whose only weapons are the strength of their arguments. Incapable of putting forward one sole piece of advice, I am restricting myself to pointing out this particular observation: the man in the position of power will only change when those whose exploitation he is dependent upon manage to escape or, at the very least, shift their position slightly, leaving without a base. In essence, once this shift happens they are then faced with a life or death question, and will finally see the importance of taking charge, by themselves, of their fate.

My personal intention is this: to speak, and to write for us. We will be closer to true liberation if, instead of paying attention to our enemies or entering in their game of constant competition and annihilation, we choose, like the great female writers in literature, to foster amongst ourselves an understanding that allows us to build bridges which move beyond the constraints of time and space, beyond old and new walls. We will be closer to it, still, if we dare to revive, understand and console the child that we were; if we view literature as the most powerful vehicle of love and solidarity, and if we try to write it for those whom still today need these things as they need air to breathe.

To read the original in Spanish, please see http://blog.eternacadencia.com.ar/archives/34072 where it was originally published.

Submit a Comment